I gave a 25ish-minute talk at PyCascades 2022 covering a Django app that Jamey Sharp built and I supported for the Portland GDC. My script and slides are below. Please note that this is not an exact script; I had to cut some material from my talk during recording to get it closer to the time limit that I’ve left in this version of the script. Consider it a little bonus material! You can watch a video of the talk on YouTube or below:

I’m here to talk about my experiences doing bail and legal support for protestors arrested in 2020 and 2021 during the George Floyd Uprising. Since I’m White and I’m talking about supporting people arrested while asking for racial justice, I need to say that I’m only talking about the specific project I worked on. I didn’t organize or lead protests or anything like that. Please consider this a report back on the small chunk of mutual aid that I worked and nothing more. Furthermore, I did not do this work alone. This talk covers the efforts of dozens of people who I am proud to work alongside.

This talk covers technical topics, but it also includes discussions of institutionalized racism and police violence. If you’re not in a place where you can hear about these topics, please consider stepping away for the moment. You can always watch the recording later.

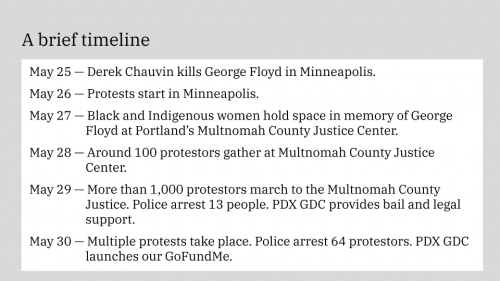

On May 25th, 2020, George Floyd went to a grocery store in Minneapolis and made a purchase. Thirty-one minutes later, he was dead at the hands of a police officer.

On May 26th, hundreds of protestors took to the streets in Minneapolis, demanding accountability for Floyd’s death — and the long list of other deaths of Black people at the hands of police officers.

On May 27th, a small group of Black and Indigenous women gathered in Portland at the Multnomah County Justice Center to hold space in memory of Floyd.

On May 28th, around 100 people gathered at the same building, with some people sitting in the doorways. Riot police violently pushed people away from the building.

On May 29th, over 1,000 people gathered at Peninsula Park in North Portland and marched into downtown to gather again at the Justice Center. Portland police officers arrested 13 people.

The Portland General Defense Committee immediately started posting bail for protestors who were arrested. The GDC started as a legal defense organization for union organizers and workers. Members of the Industrial Workers of the World founded the GDC in 1917. The Portland branch started in 2017 and has provided jail and legal support to protestors since its start. We did the same things for folks arrested on May 29 that we did for past protests: We made a spreadsheet of people arrested and started figuring out who needed bail money, including prioritizing arrestees by relative risks at the jail. Those risks included whether the person arrested was Black or Indigenous, LGBTQ, or had health risks.

Dealing with thirteen arrests at once was a stretch for us. At that point, we were used to two or three arrests at one event and supporting maybe two people with ongoing cases at any given time. We were able to pull together bail funds from members and friends, but we knew we would need to raise money to cover legal costs and reduce the bail burden we’d already taken on. Prior to 2020, the Portland GDC had a budget of a few thousand dollars per year. I put up a GoFundMe early on May 30th. By the end of that day, police had arrested 64 people.

Protests continued every night into January 2021. I’ve heard estimates that 70,000 people participated over those eight months. Portland still sees several protests and rallies around racial justice every month. Local police and federal law enforcement agents made over 1,000 arrests at protests in Portland. They beat, gassed, and otherwise hurt countless protestors and journalists.

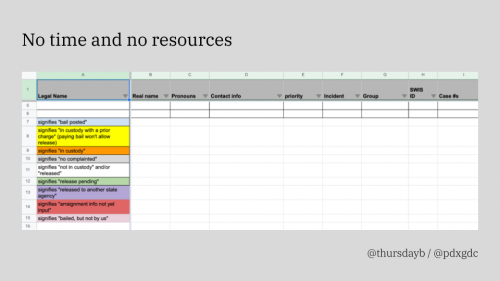

As you can guess, gathering and managing information on who had been arrested, who needed bail money, and where each person was in the legal process outgrew a single spreadsheet rapidly. On June 6th, 2020, I contacted on Jamey Sharp, who I knew from various tech-related things here in Portland and asked for help. I was deep in the weeds at that point and basically gave Jamey free rein to figure out how to replace this terrible spreadsheet with something that could manage information better. We were not in a position to pay Jamey and I am eternally grateful he was able to help us. The Portland GDC still has minimal resources beyond dedicated volunteers and some funds earmarked for legal expenses. While we eventually raised over a million dollars, that money is all for to bail and legal expenses and therefore not available for administrative costs like building software applications.

One of the reasons I reached out to Jamey is because of his experience scraping all kinds of websites. He was unable to speak at this event, but I encourage you to check out his project Comic Rocket at comic-rocket.com, which is one of the places he got that experience. I figured Jamey would be able to automate some of our information gathering, letting volunteers focus on things technology can’t do. Jamey’s experience meant that he had the first iteration of our app up and running on June 12, with all the notes in our terrible spreadsheet imported and ready for us to work on.

As the summer of 2020 wore on, we added users and functionality and scaled up a little just about every day. The Portland GDC’s workflow constantly changed based on capacity and the growing number of arrests. This was not a situation where a developer got to make nice neat little upgrades and slowly roll them out to users. This was duct-taping steering to an airplane that was already in flight and occasionally doing barrel rolls.

The web app we use for the Portland GDC’s work can be thought of as two key pieces. Most people only ever see an interface to a database, listing people who were arrested with a bunch of fields about their contact information, the status of their court case, and various other details. It’s an amped-up, search-friendly spreadsheet.

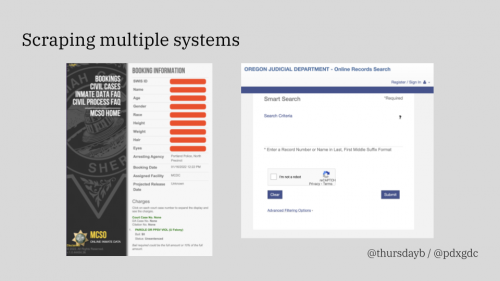

But the app also pulls in information from several sources, automatically prepopulating many of those fields and providing updates to volunteers. Those sources generally don’t have APIs, so the app scrapes them. The sources include Oregon state court records and jail records from the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office. MCSO is responsible for processing anyone arrested on state charges and many of those arrested on federal charges in Multnomah County (which includes the majority of the city of Portland).

The information we need to do our work comes in an absurd variety of formats, with an equally absurd set of access requirements. For instance, a lot of court information is in PDFs that are scans of printed documents, often with important handwritten notes like “Dropped” to indicate a suspended charge.

Federal courts work differently than state courts. and have less public information that can be scraped. Federal court cases go through PACER, which is an app that charges 10 cents per page when you access a document, as well as fees for search results and non-case specific reports. 18F, the federal government’s in-house technical consultancy, has looked at upgrading the system but their report is best summarized as no one knows how PACER works, it’s unmaintainable, and we need something entirely new and built from scratch.

Important information also disappears regularly. MCSO’s arrest information will change with no warning and no record if someone at the jail updates information, including during the booking process. Records of arrests drop off the site entirely after a few weeks. There’s also no listing of citations — incidents where protestors are charged with a crime, usually a misdemeanor, but not arrested. And the information is available is often full of errors. Information collected during arrests is the worst. We’ve known for a long time that law enforcement agents will “tweak” certain information they collect to make their own stats look better. But the data we saw from protests made those changes much more obvious. Police record the races of people arrested incorrectly constantly. In particular, we’ve seen glaring errors around the race of people of color, which have allowed the Portland Police Bureau and other agencies to claim that almost all protestors arrested in Portland are White. We’ve also seen names, genders, physical descriptions, and more recorded incorrectly.

We’ve had to figure out the meanings of certain data through trial and error because there’s not any documentation available. MCSO also uses different terms and definitions for specific charges than the Oregon court system uses, to the point that our app only grabs the statute number a person is charged under and maps it to correct charge information in our database.

This system is especially infuriating when you realize that it’s on the people who are arrested to correct any errors. Since errors can have consequences that include being kept in jail, they can be impossible to correct without expert legal help. People who are arrested are also expected to stay up to date on their cases, without any of the modern notification systems you might expect. If someone’s charges are suspended, that person is instructed to call the district attorney’s office at least monthly to check if their charges have been reinstated for at least the next two years. If they don’t, they’ll likely miss a court case which will result in a warrant being issued for their arrest and other terrible outcomes. COVID has also meant that policies change constantly, often without online notice. Even before the pandemic, details around court hearings routinely changed on the day of, but as things moved online, everything about legal processes got more complicated.

These websites are also delicate. Some were constructed by contractors trying to keep costs down, while others are built by companies that know that they can take advantage of people who are incarcerated without anyone important caring.

Django and Python were the logical choices for this project for a few reasons: First, Jamey had already built Django apps and was pretty familiar with the framework. And while I haven’t built a whole Django app by myself, I’ve gone through some workshops. Second, Django’s built-in admin interface makes managing a bunch of structured data really easy. The user interface enables anyone to edit that data without tons of training. Jamey was also already familiar with Scrapy, a Python scraping framework, so he could get that set up with a Django-based app quickly.

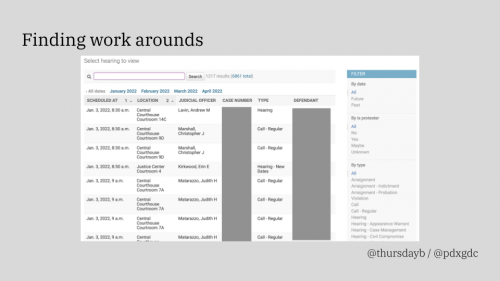

One of the pieces of information we need to grab automatically are upcoming court dates. The Oregon court calendar site is particularly irksome. Jamey jumped through lots of programmatic hoops to get that scraper running: the site limits search to 550 results, without offering any “next page” button. The scraper can’t just grab all calendar entries over the next 3 months without hammering the site harder than we want to. So the solution is a little complicated: the scraper looks at the specific case numbers we care about, then groups all the cases with the same starting numbers, trimming off the last two digits. When the court calendar is queried with those truncated group numbers, there are a max of 100 active cases returned. By batching together cases, the scraper minimizes the number of queries — though Jamey has pointed out that if whoever designed the court calendar site had just limited to search results to 1,000 rows instead of 550, he could have cut the number of queries even further.

Of course, there’s still plenty of work that requires a human touch. We have to audit our data regularly, adding in pieces that MCSO missed or that come from conversations with the protestors we’re supporting. Django has made those audits relatively simple, even though they still require a lot of reading through information for the humans involved. We can use tags for indicating the specific categories that need auditing at a given time, as well as sort and filter information in a variety of ways.

The Portland GDC is not a large organization, even now. We’re also not an especially technical group. We recruited volunteers to work on legal support in July and August of 2020, and more volunteers have joined since then.

In preparing this talk, I asked folks who use the app regularly what technical knowledge they had before volunteering with the GDC. The range was even wider than I expected. One of our most technical volunteers (other than Jamey and myself) came in knowing some JavaScript and could use the command line. But we also had folks with very little technical experience, who might use Google Docs or email, but not much else. With some onboarding and documentation, they were all able to make use of the app, as well as suggest improvements that would make our work easier.

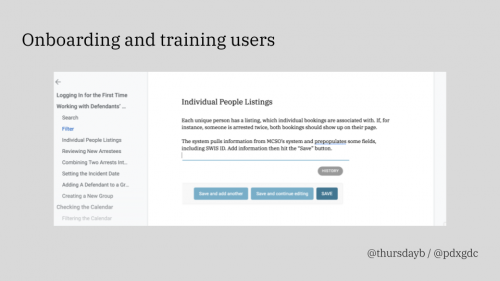

All onboarding, and all other work for that matter, happens remotely. Django’s user interface is reasonably simple right out of the box and while we’ve tweaked the user experience lightly, Django uses a visual language in interfaces that is very similar to what’s considered “standard” on the internet.

I created our technical onboarding process. Another person was responsible for walking new folks through specific support situations, communication norms, and our policies, so I was able to focus just on getting people on to the app.

I do a video call with each new user that includes a 30-minute walk through of the app. We actually don’t always need the full 30 minutes, but we set up user accounts during that session and getting folks through their first time logging in was often hard — in fact, it was the point our users struggled with the most. That’s because some of our account setup emails wind up in spam. So I built in time to search around for emails. I also limited onboarding sessions to a max of three new users because I only have enough patience to go through three people’s spam folders at a time.

During the walk through session, we go through each section of the app as well as our documentation. Our documentation is a shared Google Doc with screenshots and written descriptions — it’s not fancy, but it does contain answers to basically every question anyone has asked me about the app.

We tweaked the app as users asked questions and needed more features. Jamey wisely pushed back every so often and reminded us of our options, even deleting certain features when they were no longer needed. If Jamey hadn’t provided a technical voice of reason, we’d probably have a full-featured CRM at this point, even though that’s not what we need.

And when I checked in with our users while getting ready to give this talk, they told me that the app was intuitive, friendly, hard to break, and empowering. Users felt empowered to work with data, even if they didn’t come in knowing tech, legal proceedings, or activism. Some features still don’t get used as much as possible. But volunteers say this is more about the time available to do work, not due to difficulties with the app. People also like that they don’t feel beholden to the app and that it’s not judgmental about unfilled fields. One person even said that using the app reminds them of using a message board because they can see the notes and work of other volunteers, which helps them stay connected through all this remote work.

We realized early on that we were sitting on a pile of valuable information. While most of what we pulled together was publicly available, it wasn’t combined in this way anywhere else. Between what we scrape and the information we add from the people we’re supporting, we created a doxxer’s paradise. Not only do we have data like physical addresses and phone numbers, but we also have notes on who needs what kinds of help. The risks of holding this information are massive. If someone with bad intentions got access, they’d be able to easily harass people both online and offline. We have an ethical obligation to mitigate every risk we can and to protect this information. The alternative is compounding the harm legal systems are already doing to folks.

We also faced a lesser risk of losing access to the sources where we pull information from. That did happen several times — not only does MCSO remove information from their arrest records, but the Oregon court system stopped allowing access by anything with an IP address located outside of the US, which coincidentally enough included us at the time. Jamey found us work-arounds, but I’m always waiting for the next time one of these systems changes their access controls. We also faced concerted attacks on any tool we publicly use: we dealt with numerous malicious reports to GoFundMe, Twitter, our email provider, and more.

We reduced our risks in several ways. First off: we obviously didn’t go around telling people about this app. After all, if someone is attacking your email, they’ll attack every other system they can find related to your organization. We’re facing less attention online now, so talking about the app here is a calculated risk that we’re comfortable with — but I’m not telling you who hosts the app or other important details to keep those risks to a minimum.

We also look closely at everyone who gets access to the app. Our due-diligence process for volunteers includes an in-depth internet background search and confirmation of the information we find with shared connections where possible. Jamey was also able to set up multiple types of user accounts so that we could limit each volunteer’s access to information they actually need to do their work. If, for instance, someone is writing letters of support to people who are currently incarcerated, they can only see those people in the system who they’re writing to. Those volunteers don’t get much more than an address and some biographical information.

Technical security is, of course, an aspect of risk mitigation. Django has good security features out of the box, assuming you use them. By using Django, we could use built-in security options and also access documentation that we could adapt to explain what was going on behind the scenes to volunteers. But the most important step to managing our security concerns was our effort to avoid collecting information that we didn’t feel we could protect — and that policy would have been the same no matter what framework or language the app was written in. No technology choice is as important as defining what data you’ll collect and how it will be handled.

One of our biggest ongoing issues was burn out. Basically everyone burnt out over the course of 2020 and 2021 — doing legal support just made us burn out faster. We’ve had higher turnover among volunteers than I’d like, but this is hard work. Even though we don’t need to worry too much about gathering and processing data, we’re dealing with emotional situations and even the best outcomes for the people we’re working with involve lots of time dealing with an adversarial legal system.

The only way to handle the fluctuations in capacity is to document EVERYTHING. Everything that happens in an individual case gets recorded in the app. Everything about the app gets documented, too. Our documentation isn’t fancy: it’s a document that I add questions and answers to whenever an app user asked me something. I lifted some pieces out of the Django documentation and reworded them a bit to ensure our users understood how to handle a problem even if they didn’t come in with a ton of technical experience. And any time an edge case came up, I took tons of notes.

I did worry a lot about what would happen when Jamey and I burned out, however. We both managed to hang on until the app was basically stable and there hadn’t been any new features needed in a while. I did want to make sure that someone had enough knowledge to at least decide if a situation was an emergency and to have someone who could step up if such an emergency came to pass. Luckily, our most technical volunteers reached a point with the app where they seemed capable of handling questions and I drafted a back-up developer who would be willing to handle emergencies before I had to take a break.

I think the work I’ve done with the Portland GDC over the past two years is some of the most important work I have done or will do. We put together legal support for hundreds of protestors out of Django, duct tape, and donations from strangers. We did our part to ensure that protestors could be in the streets for months on end and reduced the risks they faced. One of the most meaningful measures of our work, at least for me, is that Rodney Floyd, George Floyd’s brother, thanked Portland protestors specifically last April. He said the support of protestors meant so much to their family and that staying in the streets helped ensure his brother’s killers faced justice.

So here’s where everything stands as of February 2022: Mike Schmidt, the district attorney here, suspended most protest-related charges. That’s not the same thing as dropping charges entirely. Instead of dropping charges, he’s just not currently prosecuting charges. The DA has the option to reinstate suspended charges for years to come. He’s already reinstated a few. By suspending charges, rather than dropping them, the state also gets to hold on to bail money and evidence until the charges age out. And since almost $700,000 of the money the Portland GDC raised went to posting bail for hundreds of protestors, that money is not available for legal fees or bail for future protests for an indeterminate amount of time. Schmidt is considered a very progressive DA and he’s still chosen to hold protest-related charges over protestors’ heads for years to come.

The federal district attorney, Scott Asphaug, hasn’t been so nice. Several protestors are facing federal charges, with Black and Indigenous folks facing the harshest penalties. There are at least three such cases which will be going to court in the next few weeks with each defendant facing years in jail. It’s also worth noting that Asphaug previously worked for the Portland police union to get police officers out of trouble during internal investigations and the U.S. Department of Justice does not consider that relationship a conflict of interest.

The city of Portland, as well as several federal agencies, are facing lawsuits from many of the protestors who police attacked. Residents of Portland who were not involved with protests but were teargassed or otherwise harmed are also bringing their own lawsuits. While a few cases have already been settled with payouts by the relevant government agency, many seem to be going to court.

While Portlanders are no longer protesting in the streets every night, cases related to the George Floyd Uprising won’t be over for months, perhaps even longer. The Portland GDC is still doing legal support and expects to be doing prison support for folks unjustly incarcerated over these protests for years to come.

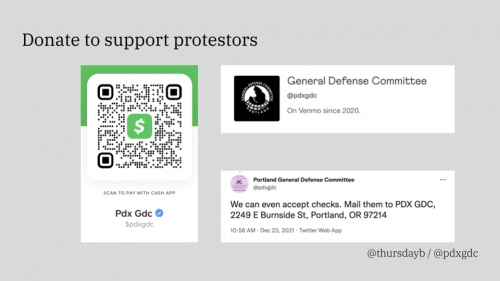

I hope you found this talk valuable, both in terms of learning about launching a Django app with minimal resources and even less time and in terms of understanding the amount of work it takes to support protestors through arrests and court cases. The Portland GDC continues to support people arrested at protests in 2020 and 2021 and if you’re able to, please consider donating to help cover the legal costs that many protestors are still dealing with. You can donate through CashApp, Venmo, or by mail to PDX GDC, 2249 East Burnside Street, Portland, OR 97214.